Storytelling at Ringling College of Art & Design

With the creation of Web 2.0 and the hosting of user-generated content sites, social networking media sites, alternate world sites, plus with the popularity of gaming today, the art of storytelling has exploded exponentially. Stories today can and do cross from books to movies to websites, mobile devices, print, video, games and even to ads.

The writing universe has expanded such that today's storytellers may identify themselves across a range of possible genres, including (but not limited to): novelist, playwright, game writer, screenwriter, graphic novelist, digital storyteller, short story writer, animation writer, ad design storyteller, children's book writer, or interactive and cross-platform storyteller.

What does a good story need?

Anchored - Lindsey Olivares

Kiwi! - Dony Permedi

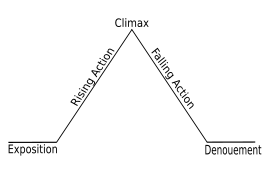

Freytag's pyramid

A Story is usually divided into five parts:

Exposition

The exposition provides the background information needed to properly understand the story, such as the protagonist, the antagonist, the basic conflict, and the setting.

The exposition ends with the inciting moment, which is the incident without which there would be no story. The inciting moment sets the remainder of the story in motion beginning with the second act, the rising action.

Rising action

During rising action, the basic internal conflict is complicated by the introduction of related secondary conflicts, including various obstacles that frustrate the protagonist's attempt to reach his goal. Secondary conflicts can include adversaries of lesser importance than the story’s antagonist, who may work with the antagonist or separately, by and for themselves or actions unknown.

Climax

The third act is that of the climax, or turning point, which marks a change, for the better or the worse, in the protagonist’s affairs. If the story is a comedy, things will have gone badly for the protagonist up to this point; now, the tide, so to speak, will turn, and things will begin to go well for him or her. If the story is a tragedy, the opposite state of affairs will ensue, with things going from good to bad for the protagonist.

Falling action

During the falling action, which is the moment of reversal after the climax, the conflict between the protagonist and the antagonist unravels, with the protagonist winning or losing against the antagonist. The falling action might contain a moment of final suspense, during which the final outcome of the conflict is in doubt or resolution. In this case the pyramid (as having a triangle form) has to be modified.

Dénouement or catastrophe or Resolution

The comedy ends with a dénouement (a conclusion) in which the protagonist is better off than at the story’s outset. The tragedy ends with a catastrophe in which the protagonist is worse off than at the beginning of the narrative.